Münsterberg would surface in the comics as Wonder Woman’s archenemy, Dr. Marston was a lab assistant to the prominent Harvard psychologist Hugo Münsterberg, a rigid German who opposed votes for women and thought educating them was a waste of time. His experiences in the psychology department left their mark, too. Maybe that’s where his fusion of feminism and bondage started-imagery of slavery and shackles abounded in the movement’s demonstrations and propaganda. As an undergraduate at Harvard just before World War I, he was thrilled by militant suffragists like the ones who chained themselves to the fence outside 10 Downing Street. The only scion of a once-grand Boston family, Marston was equal parts genius, charlatan, and kinkster. William Moulton Marston invented the lie detector-a forerunner of Wonder Woman’s golden lasso. Sanger’s influence is perhaps the most important of the connections that Lepore teases out between Wonder Woman, the early-20th-century women’s movement, and Marston’s fascinating life and odd psyche, in which the liberation of women somehow got all mixed up with bondage and spanking. Olive Byrne was the niece of Margaret Sanger, whose youthful brand of romantic, socialist-pacifist feminism was formative for Marston. And Lepore adds another catalyst to the mix.

Make that creators: not the least of Lepore’s revelations is that Marston had a lot of help from his wife, Elizabeth Holloway (we have her to thank for “Suffering Sappho,” “Great Hera,” and other Amazonian expostulations), as well as from his former student Olive Byrne, with whom he and Holloway lived in a permanent ménage à trois that produced four children-two from each woman. In her hugely entertaining new book, Jill Lepore sets out to uncover the true story behind both Wonder Woman and her creator. He believed women were superior to men and should run the world-and would do so in, oh, about a thousand years. William Moulton Marston, the inventor of Wonder Woman, would have loved that cover.

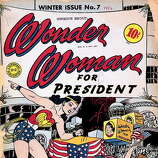

The most popular superheroine ever had to wait for the next issue to stride through the sky in all her 1940s Amazonian glory under the headline “Wonder Woman for President.” Below her is a divided scene-one half a war-torn landscape, the other a pleasant street featuring a billboard that reads Peace and Justice in ’72. That honor went to the many-armed Hindu goddess Kali, holding a frying pan, a typewriter, a mirror, and other tools of the hyper-multitasking modern woman. magazine (spring 1972), although many remember it that way. Wonder Woman did not grace the very first cover of Ms.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)